- Small Dog Place Home

- Diseases

- Giardia in Dogs

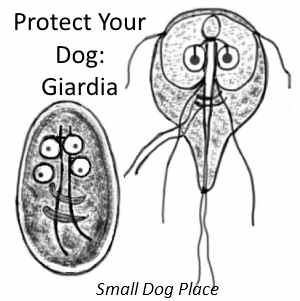

Giardia in Dogs: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment & Prevention

Written and reviewed by Janice Jones, former veterinary technician

Last medically reviewed: January 2026

As parasites go, Giardia in dogs is a common intestinal parasite that is not only difficult to get rid of but also causes vomiting and diarrhea, especially in young puppies

What is this Parasite?

Giardia in dogs is another annoying parasite that can affect your dog’s health. This small protozoan, Giardia, is not a worm but a one-celled organism that can also cause harm in many animals, including people, although it’s not entirely clear how common transmission between dogs and people is.

It is a very common parasite found in dogs, cats, horses, pigs, cows, sheep, and goats. The resultant disease is called giardiasis.

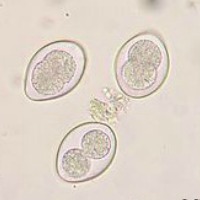

Giardia in Dogs: Cyst and trophozoite life-stages

Giardia in Dogs: Cyst and trophozoite life-stagesHow Do I and my Dog Get this Parasite?

People get Giardia when they sample contaminated water, usually on a camping trip, and the resulting vomiting and diarrhea is called traveler’s diarrhea.

If you are an outdoors type of person, you might have heard of beaver fever or backpacker's disease. These are all caused by the Giardia organism.

In dogs, the most common form of transmission is through the fecal—oral route, where dogs come into contact with infected feces, water, or surfaces that contain Giardia cysts. They can do this by eating the cysts directly, sniffing infected poop and then licking their lips, or drinking contaminated water.

The infection is easy to pick up because Giardia cysts are highly resilient and immediately contagious after another animal excretes them.

When humidity is high, the survival rate of the cysts increases, and when there are more animals in the area, infection becomes much more likely. This is why you see these infections in shelter dogs, pet stores, and multiple dog homes.

Life Cycle of Giardia in Dogs

There are still gaps in our understanding of this one-celled organism's life cycle. This protozoan appears to have a two-stage life cycle.

To begin an infection, a dog ingests a cyst, usually through eating poop, infected grass, or drinking contaminated water. The cyst passes through to the dog’s small intestine, where it opens up and releases an active version called a trophozoite.

During this stage, the tiny organism is motile and lives in the small intestine of its host. Here it attaches itself and dines on the cells lining the intestines. This causes poor digestion, which leads to diarrhea. This stage will be reproduced by division, and many will form hard cysts around them.

These cysts are then shed in the stool, where they can infect another dog or other animal that comes in contact with the infected feces. Once the second dog swallows the cyst, it migrates to the small intestine, and the process begins again.

This hardy cyst phase can persist in the environment for several months, especially in water and damp environments.

Giardia in dogs is common, but it also occurs in farm animals and people. There seem to be different groupings of these organisms called Assemblages that affect different species of animals.

For example, dogs tend to have assemblages C and D, cats are infected by A1 and F, and humans are normally more susceptible to A2 and B.

This is good news for people since it is possible to contract Giardia from dogs; it is not likely, but again, there is much to learn about this parasite. When humans acquire this type of infection, it is usually due to contact with contamination from human waste.

This often occurs when Giardia enters the public water supply. Outbreaks have been known to occur even in day care centers where hygiene practices break down.

Symptoms of Giardiasis in Dogs

Some dogs carry Giardia without showing obvious symptoms, which can make diagnosis challenging.

- Foul smelling feces

- Diarrhea with some mucus and/or blood

- Vomiting

- Sometimes Fever

- Loss of weight if not treated

If your dog has foul-smelling diarrhea, which can range from soft to watery with traces of mucus, he might have Giardia. Sometimes blood is seen in the stool.

Vomiting is another symptom, and sometimes fever. If symptoms persist, the dog may also lose weight. Often, dogs infected with Giardia show no symptoms.

In most healthy dogs, giardiasis is not considered life-threatening, but it can be more serious in puppies or immunocompromised dogs.

Diagnosis of Giardia in Dogs

Diagnosis often requires a combination of testing methods and clinical judgment.

You will not be able to diagnose this yourself, as the parasite is microscopic and only detected through laboratory tests that are performed by a veterinary hospital or an outside laboratory. Giardia is often misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed because it is difficult to see.

There are several ways to observe the cysts, but since cysts are not shed continually, it is possible to receive several negative test results, yet still have the disease.

Several tests are often used, including a direct smear of a fresh, unrefrigerated sample, fecal flotation, and a fecal ELISA called the Snap® Test.

If a fresh sample is examined under the microscope, the more active form, the trophozoite, can sometimes be seen moving. When a fecal flotation method is done, the vet tech is looking for the cyst stage.

Unfortunately, both positive and negative results can be confusing. Many dogs may shed cysts without symptoms, whereas some with symptoms and the disease may not shed any cysts on the day of the test.

Some veterinarians will repeat a test that has negative results when the dog shows the classic symptoms.

Drug Treatment for Giardia in Dogs

Treatment decisions are based on symptoms, test results, and the dog’s overall health. Your veterinarian will determine the most appropriate approach.

Treatment approaches can vary among veterinarians based on clinical findings and risk assessment.

How and when to treat? Some vets will treat even with a negative test result if the dog shows other signs of the disease, because there is a potential for human infection.

There are several drugs on the market that treat the infection, but all require multiple days of medication.

Metronidazole or Flagyl

Metronidazole is an antibiotic that is given for 5 to 7 days. Under the trade name Flagyl, this older treatment is approximately 60–70% effective in some cases, but it also treats other bacterial causes of diarrhea. Side effects of this drug include vomiting, anorexia, and liver toxicity. It cannot be given to pregnant dogs.

Fenbendazole or Panacur

Fenbendazole, or Panacur, is a worming medicine or antiparasitic that also treats other types of parasites and is given for 5 days to treat giardia. This is considered to be safe in young puppies at least 6 weeks old.

Sometimes, a combination of metronidazole and fenbendazole are given.

Environmental Treatment of Giardia in Dogs

Bathing is also required to remove fecal debris and eliminate any cysts that might remain on the dog’s hair or fur. When there are other dogs in the household, they all may be treated at the same time. A regular dog shampoo is usually sufficient to remove all fecal debris.

It is difficult to decontaminate soil and grass, or to remove standing water, in the outdoor area. Cysts will not survive in dry conditions, but prompt removal of feces will help eliminate the problem, at least in areas with little rainfall. In moist or wet areas, it is nearly impossible to eliminate the threat entirely, but promptly removing the dog’s poop will help.

Inside, any surfaces the dog comes in contact with can be cleaned and sanitized using steam cleaning or disinfectants.

For disinfecting surfaces, such as floors or crates, you can use chlorine bleach at a rate of 1-2 cups per gallon of water. Always follow product labels and avoid mixing cleaning agents. If unsure, ask your veterinarian for guidance.

Other chemicals, such as quaternary ammonium or Lysol, work well to kill the cysts. Clean, disinfect, and allow to air dry before allowing your dog to have access to the area.

The longer the disinfectant stays on the surface, the better the chances that all cysts will be killed. Ten minutes is usually a good ballpark figure to aim for if you are spraying with a bleach solution

Public Health Concerns of Giardia in Dog

While transmission from dogs is possible, it appears to be uncommon.

People with diseases that may increase their susceptibility to infection should limit exposure to dogs being treated for Giardia. We are including people in this category who are immunodeficient, such as those with AIDS or cancer, or those who are undergoing chemotherapy.

If you do develop gastrointestinal symptoms after being exposed to an infected dog, it would be advisable to seek medical attention.

Always wash your hands before and after feeding and handling the dog, and of course, after cleaning up soiled areas.

If you have children, encourage them to wash their hands regularly, especially after playing with their dog.

References and Further Reading on Giardia in dogs

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention

Other Types of Parasites in Dogs

More About Janice (author and voice behind this site)

Janice Jones has lived with dogs and cats for most of her life and worked as a veterinary technician for over a decade.

She has also been a small-breed dog breeder and rescue advocate and holds academic degrees in psychology, biology, nursing, and mental health counseling.

Her work focuses on helping dog owners make informed, responsible decisions rooted in experience, education, and compassion.

When not writing, reading, or researching dog-related topics, she likes to spend time with her six Shih Tzu dogs, her husband, and her family, as well as knitting and crocheting.

She is also the voice behind Miracle Shih Tzu and Smart-Knit-Crocheting

Free Monthly Newsletter

Sign Up for Our Free Newsletter and get our Free Gift to You.

my E-book, The Top 10 Mistakes People Make When Choosing a Dog (and how to avoid them)